28. juni, Vidovdan, ili Vidovden, veliki je praznik u Srbiji i u Bugarskoj. 28. juni, Vidovdan, tuzan je i tezak dan za sprski narod.

Na taj dan, po kalendaru koji je važeci kod Srba današnjice i po kojem se beleže svi važni dogadjaji koji su nas kroz istoriju pratili i koji nas čine onim što osećamo da jesmo, na taj dan, a u pokušaju da od Osmanlija odbrani Srbe i zemlje srpske, 1389. godine poginuo je Knez Lazar i stradala je srpska vojska. Raspalo se veliko srpsko carstvo, počela je velika seoba Srba, a sa njom i prenošenje Lazarevih mošti, od manastira Ravanica, gde je originalno sahranjen, preko Fruške Gore do Beograda, posle do Kosova, pa opet nazad do Ravanice.

Istorija kaže da je srednjovekovna Srbija bila veličine SFR Jugoslavje, da je njena centripetalna sila bo car Dušan Silni, a da je njegovo carstvo trajalo samo onoliko koliko i on sam. Prebrzo sagradjeno, prebrzo prošireno, bez vremena da se konsoliduje, pucalo je po šavovima punih razlika, dok, kao i mnoga druga, novija, nama bliza i poznatija, kao i ona dalja, starija carstva, nije palo kao žrtva poznatog sindroma ambicioznosti mnogih velikih lidera i velikih ratnika.

Slučajno ili ne, krenuli smo na Vidovdan, sad već davne 1993. Našem odlasku prethodilo je pucanje po šavovima SFR Jugoslavije, prebrzo sagradjene, prebrzo proširene, zemlje čija je centripetalna sila bio Tito, zemlje koja je trajala koliko je trajao i on na njenom vrhu, zemlje koja je imala nedovoljno vremena za konsolidaciju svojih krajnosti, zemlje koja je, kao i srednjovekovna Srbija, bila žrtva poznatog sindroma ambicioznosti velikih lidera i velikih ratnika i kao takva, propadala.

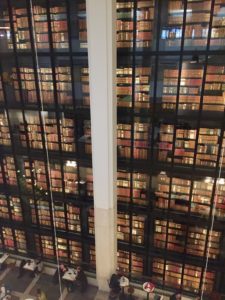

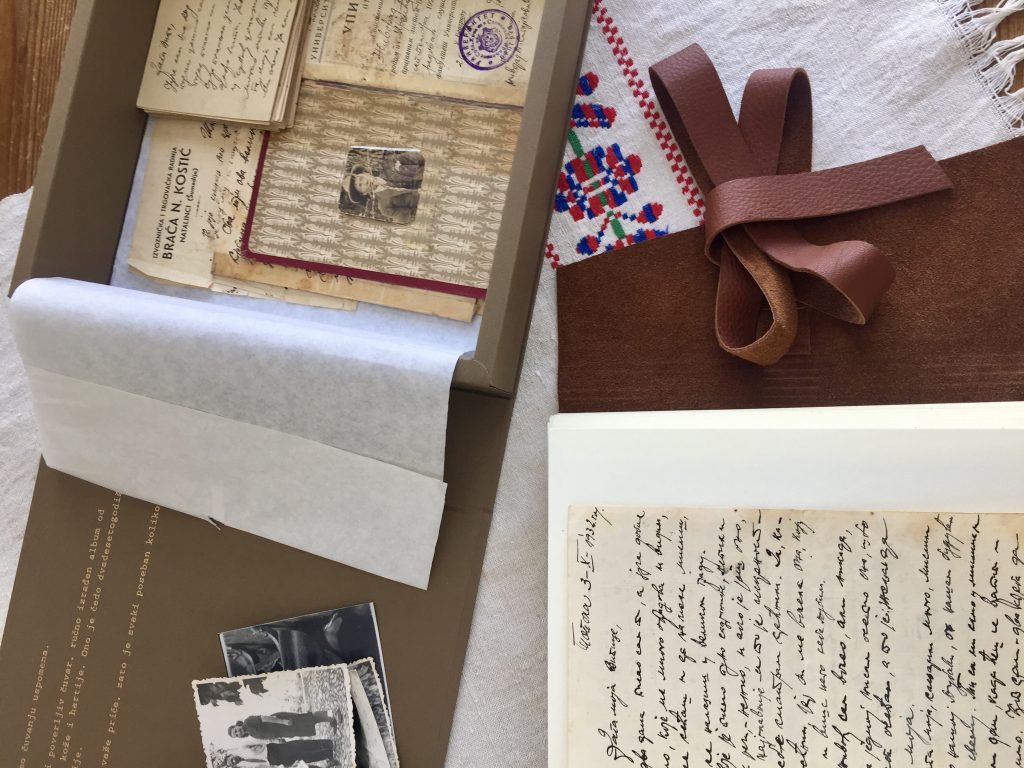

Krenuli smo noću, autobusom do Bugarske, tek odatle avionom dalje. Aerodrom u Sofiji jedan je od najtužinijih na kojima sam bila, ali u to vreme činio mi se najbolji na svetu. Počela je još jedna od velikih seoba Srba pri kojoj se nosi samo najnužnije, ono bez čega se, što razumom, što srcem, zaista ne može. Nas četvoro, dvoje velikih i dve male, nekoliko improvizovanih torbi punih dragunlija poput džempera, tiganja, pelena i kašika, poneka knjiga, dubak, kolica i fotografije. Fotografije naše neprikosnovene, bez kojih su, samo par godina ranije, u prethodnoj velikoj seobi krenuli moji roditelji, pa nismo to mogli, a nismo ni smeli to uraditi i mi. Moralo se nekako, tamo negde daleko, znati ko smo, šta smo i čiji smo bili.

Ce qu’a été le notre une fois

(Le) 28. juin, Vidovdan, ou Vidovden, c’est une grande fête en Serbie et en Bulgarie. (Le) 28. juin, Vidovdan, un jour triste, un jour dur (pour les) des peuple serbes.

Ce jour-là, selon l’ancien calendrier de l’église serbe, et selon le calendrier qu’on utilise pour marquer tous les événements d’importance historique et religieuse qu’on suit, et qui nous font (d’) être ce que nous sentons que nous sommes, ce jour- là, en 1389., en essayant de protéger son peuple et son pays serbe des Ottomans, le prince Lazar était tué et l’armée serbe était détruite. Cet événement a marqué la chute du grand empire serbe, la grande migration des Serbes a commencé bientôt, et, avec elle, le transfert des reliques de prince Lazar de son endroit d’enterrement original, au monastère Ravanica, ensuite sur Fruška Gora, à Belgrade et au Kosovo, et, finalement, de nouveau à Ravanica.

L’histoire dit que la Serbie de Moyen Âge était de la taille de SFR Yougoslavie, que le tsar Dusan Puissant était sa force centripète, et que son royaume a duré seulement aussi longtemps que lui. Construit trop rapidement, élargi trop rapidement, sans le temps de se consolider, le royaume se déchirait aux coutures qui étaient pleines de différences jusqu’à ce qu’il ne tombe victime de l’ambition bien connue des grands leaders et des grands guerriers.

Par hasard ou pas, on est parti le jour de Vidovdan, l’année 1993. Ce qui a précédé à notre départ, c’était la déchirure des coutures de RSF Yougoslavie, construite très rapidement, élargie très rapidement, le pays dont la force centripète était Tito, le pays qui a duré autant que lui sur son sommet, le pays qui n’avait pas assez de temps pour la consolidation de ses extrêmes, le pays qui était, telle que la Serbie de Moyen Âge, la victime de l’ambition bien connue des grands leaders et des grands guerriers.

Notre long périple a commencé par le bus à Bulgarie, alors seulement par l’avion, plus loin. L’aéroport à Sofia était l’un des plus tristes que je n’ai jamais vu, mais ensuite il m’a semblé le meilleur du monde. Une autre des grandes migrations des Serbes quand on porte seulement les choses les plus importantes, celles sans lesquelles il n’est pas possible de survivre ni par raison, ni par coeur. Nous quatre, deux adultes et deux filles, six valises improvisées pleines de bibelots, une poêle, quelques cuillères, la poussette, le trotteur et les couches pour bébé, quelques livres, et les photos. Nos photos indispensables, les photos qu’on ne pourrait pas laisser comme l’ont fait mes parents pendant leur dernière migration, deux années (en) avant. Il était très important de savoir (ce) qui nous sommes étés, (ce) de qui nous sommes étés, ce que nous sommes étés et d’où nous sommes étés une fois.

Ce qu’a été le notre une foi

What was ours once

The 28th of June, Vidovdan, or Vidovden, an important holiday in both Serbia and Bulgaria. The 28th of June, Vidovdan, a hard, sad day for the Serbian people.

On that day in 1389, according to the Serbian calendar for all the important historic events that to this day shape our understanding of what we were and who we are, in an attempt and with the desire to protect Serbian people and Serbian territories from the Ottomans, Serbian Prince Lazar was killed and the Serbian army was annihilated. Soon after the Great Serbian Empire fell apart, the Great Migration of Serbs took its place carrying with them Prince Lazar’s relics from the monastery Ravanica, to Fruška Gora, then to Belgrade, later to Kosovo until they were finally returned in their place of origin, the monastery Ravanica.

According to history, the medieval Serbian Empire was the size of SFR of Yugoslavia, with Tsar Dušan the Mighty as her centripetal force. Quickly built, quickly expanded, without time to consolidate its faraway corners full of differences, the empire lasted as long as the tsar himself. The Serbian Empire was fraying around the edges until, like many other old and new empires, it fell apart as a victim of the well-known ambition syndrome inherent to great leaders and great warriors.

By chance or not, we left on Vidovdan, 1993. We left while SFR of Yugoslavia, the country that was built and expanded too quickly without the time to consolidate its faraway corners full of differences, the country that was fraying around its edges. We left the country that lasted as long as Tito, its centripetal force, the country that, like the medieval Serbian Empire and many others great empires, fell apart as a victim of the known ambition syndrome inherent to the great leaders and great warriors.

We left by the night bus to Bulgaria, and only from there by plane. The airport in Sofia is probably one of the saddest I’ve ever seen, but for me, at that time, it was the best in the world. The beginning of yet another Great Migrations of Serbs, a migration in which one takes only the necessities, the necessities that one cannot live without, either by reason, or by reason of the heart. The four of us, two adults and two little girls, a few improvised suitcases full of trinkets, a frying pan, a couple of spoons, a few baby diapers, a book or two, a baby-walker, a stroller and photos – – indispensable photos because my parents left without theirs during another Great Migration just a couple of years earlier, so we couldn’t do the same. Photos that, as the essential part of our baggage, served to remind us of who we once were, what we once were and who we once belonged to.